While sharing a similar rise-and-fall pattern, there are several key differences between a regular market cycle and the wild ride offered by financial bubbles.

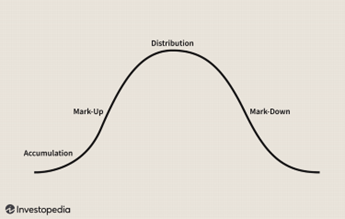

On a given day, there is one and only one certainty in the stock market: It will move. Whether that is up, down or sideways is anyone’s guess. However, when compiling information over a longer timeframe, patterns often emerge and a market cycle will begin to take shape. The components of a market cycle are often attributed to the turn of the 20th century technical analyst Richard Wyckoff. They are Accumulation, Markup, Distribution and Markdown. Generally, the pattern is:

- During accumulation early investors begin acquiring positions in an asset, the price during this time is relatively stable and range-bound; not too high, not too low.

- Markup is when there is a breakout in the accumulation phase. Trend and momentum investors see their gains as the stock price climbs higher.

- Distribution is when those early investors may begin to take their profits. There is pressure in both directions as the bullish investors and bearish investors battle for pricing supremacy.

- Finally, Markdown occurs when the sellers win out and a stock may no longer be making any higher highs despite large levels of trading volume in a stock. Some investors may hope for a brief reprieve as the price goes higher, but the overall trendline of the stock’s price is headed downward.

(A typical market cycle of accumulation, mark-up, distribution and mark-down.)

While this pattern can ebb and flow in terms of its length and magnitude, these market movements may not necessarily be completely predictable, but they are relatively reliable and follow their own internal logic. And even if the market cycle ends and markdown has been exhausted, oftentimes a new accumulation phase will take place and the cycle will repeat, albeit in a different way than the previous cycle.

But if the market cycle can be seen as a somewhat reliable, albeit temperamental member of the market family, the bubble should be considered its reckless and wild cousin. While following a pattern similar to the market cycle, their speed, magnitude and overall illogic make each bursting bubble unhappy in its own way.

A financial bubble can broadly be defined as a situation where the price of something – a single stock, a financial asset, a sector, asset class, or any scarce consumer good really (remember Beanie Babies?) – exceeds its fundamental value by a large margin. Because of this disconnect between the asset’s intrinsic value and its fundamental value is driving the asset’s price higher, bubbles don’t deflate in a slow and orderly way. Instead, they burst. Depending on how entrenched in the economy the asset is, there can be massive contagion to other sectors or even countries. The Great Financial Crisis of 2008 began because of a bubble bursting in the subprime mortgage sector and spread to nearly every inch of the globe. Not all have such far reaching effects (again, think about Beanie Babies).

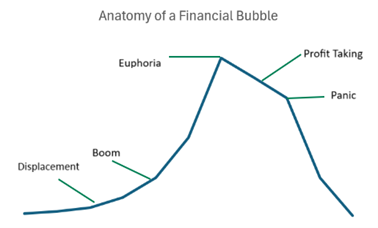

The basic outline of a bubble takes place over five stages. They are: displacement, boom, euphoria, profit taking and panic.

- Displacement occurs when investors believe there is a paradigm shift, either in new technology or a change in the economic environment. This could be the current rise of AI (it’s almost impossible to know if you’re in a bubble, they usually only reveal themselves after the fact), or when interest rates are lower for longer such as they were back in the early-to-mid-2010s. This shift is often seen by investors as the beginning of a “new normal”.

- Next comes the Boom. Prices are slow to rise, but once the thing (a stock, an economic sector, a commodity) begins to build momentum, participants begin to flood the market. The asset attracts widespread attention and that’s when FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) can send the value of what was an already growing asset to new heights as more and more investors (and even more importantly, speculators) begin to pile in.

- After the Boom comes the Euphoria. This is where gasoline gets poured on the fire and asset prices can go to the moon. Valuations reach extreme and absurd levels. This is where The Greater Fool enters the field. Prices continue to go higher because everyone who’s buying at this stage assumes that even after them, there’s a “greater fool” who is willing to buy at an even higher price.

- Coinciding with Euphoria is Profit-Taking. This is where the smart money decides that the valuation is too far removed from reality, and in anticipation of the bubble bursting, starts to sell positions and realize a profit. However, this doesn’t always mean that the top has been reached. People and markets are irrational and as John Maynard Kenyes famously stated, “Markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.” Regardless, most of the smart money has moved out and taken a profit during this time, leaving behind the dumb money and the greater fools.

- When only the fools remain, that’s when Panic sets in. During this stage, asset prices plummet; sometimes even faster than when they rose. The falling price can lead to margin calls on speculators, causing them to have to sell at any price. As the cascading effect of fewer buyers and more sellers compounds, the asset price plummets and the whole thing tumbles down in on itself, and the bubble has finally burst.

When the dust finally settles, there is oftentimes a near-complete wipeout in the value of the subject of the bubble, with regular people left holding the bag. Bubbles can last any amount of time. As long euphoria and irrationality reign, the price will go up. While it can be tempting to try to ride a golden elevator, the eventually bursting bubbles are at best a market correcting event and at worse a market manipulation scheme. Instead of chasing every new shiny thing, having a sound investment strategy that focuses on well-researched and well-understood companies whose intrinsic value is aligned with their share price, as well as having the discipline to sell when the time is right, can help mitigate such risks caused by financial bubbles.

Gavin Anderson,

Performance Analyst